"Gone With the Wind" Reconsidered: Strength, Survival, and the Shadows of the Old South

Few American movies have been revisited so many times with such interest—and debate—than Gone With the Wind. Each new watch reveals more and more about its multidimensional characters and inciting portrayal of the Civil War South. Scarlett O'Hara, Mammy, Melanie Hamilton, Prissy, Belle Watling, and Aunt Pittypat—shows how Gone With the Wind is a romance saga and a seminar on women's endurance of catastrophe and desperation.Mammy: The Conscience and the Backbone

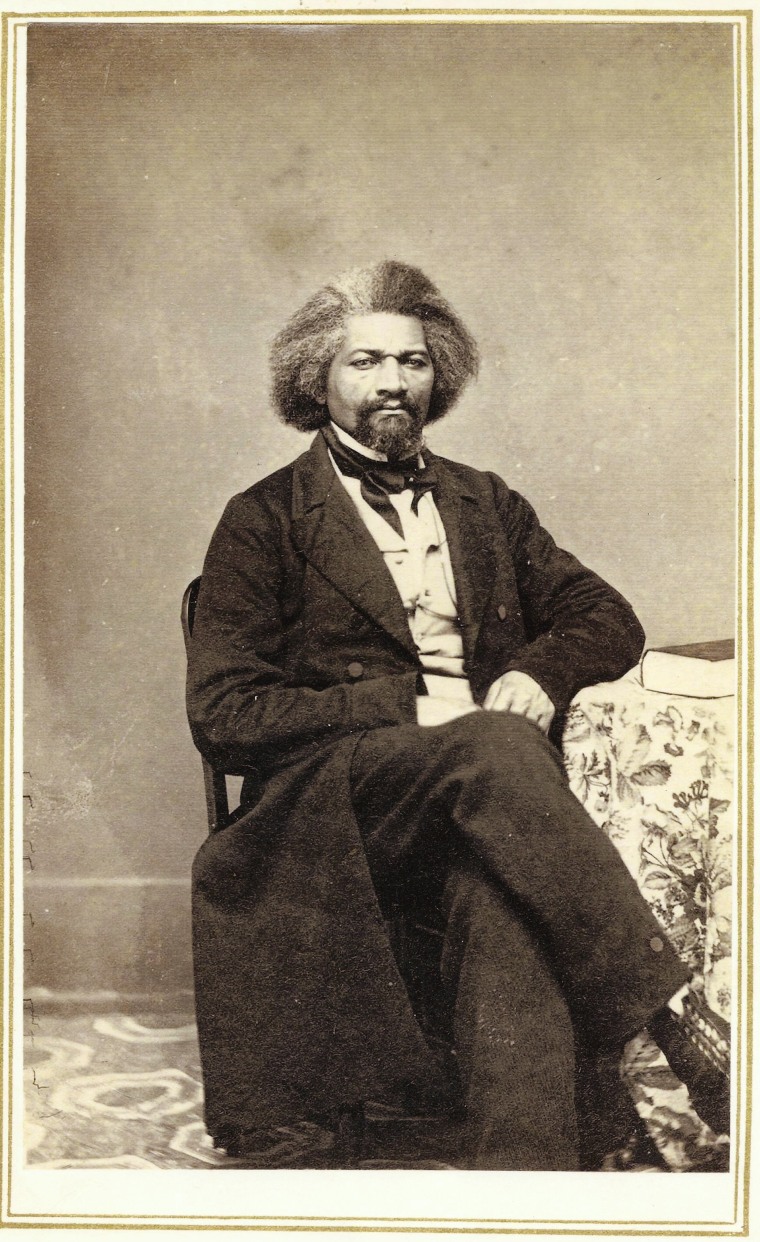

Hattie McDaniel's Mammy is still one of the movie's most powerful performances. Far beyond the stereotype of a loyal house servant. Mammy is the moral and emotional center of the film—a Greek Chorus type who berates and advises the white people around her. From her initial hot rebuke—"You ain't got the sense that God gave a squirrel! —from her staunch presence near the film's conclusion, Mammy is the real pillar of Tara. Even while the movie sentimentalizes slavery, McDaniel brings a human and authoritative presence to a figure who could otherwise have been reduced to caricature. No wonder she was the first African American to take home an Academy Award, a pioneering feat in 1939 Hollywood. Her later remark—“I’d rather make $700 a week playing a maid than $7 a day being one”—reveals a sharp awareness of her position in a racially divided industry.

Scarlett O’Hara

Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett is selfish, cunning, and often ruthless—but also a survivor. At the start, she embodies the shallow Southern belle: flirtatious, pampered, and dependent on men for validation. Yet the war strips away that illusion. Piloted to restore her family's fortunes, she becomes fiercely independent, asserting control over her own life in ways that few women in her time dared. Scarlett's transformation is typical of the manner in which wartime disruption naturally stirred women to new roles of leadership and employment. As women moved into factories and offices during World War II, Scarlett shows us that crisis can unlock resilience. Her famous vow—“As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again”—is not just personal determination; it’s a declaration of survival in a world that underestimated her.

Melanie, Belle, and the Quiet Power of Empathy

If Scarlett is fire, Melanie Hamilton is grace. Olivia de Havilland’s portrayal of Melanie offers a different kind of strength—quiet, forgiving, and compassionate. She upholds her crumbling world intact with devotion and concern, even for Scarlett, who hates and betrays her. And Belle Watling, the madam, who quietly supports Confederate troops and demonstrates more moral strength than most of the "respectable" women. Both of these women remind us that actual dignity has nothing to do with social position, and that bravery takes many forms.

Rhett Butler and the Morality of Profit

Clark Gable's Rhett Butler is a hard-nosed cynic in the face of the illusions of the Old South. War profiteering, he seethes through rose-tinted ideology that obscures other sight with catastrophe. His opportunism is an uncomfortable question: is it immoral to make money out of anarchy, or realistic? Businesses and individuals still make money now from war—be it through arms, oil, or rebuilding contracts. Rhett's character is a reminder that there will always be those who find opportunity in suffering during any war.

Facts and Lies in an Imperfect Masterpiece

Gone With the Wind certainly sugarcoats the atrocities of slavery, presenting the antebellum South in rosy tints. But beneath its flaws are commonplaces about ambition, determination, and man's frailty. One can appreciate both its artistic merit and its historical provincialism. The film is not a truthful exploration of history or race, but does present timeless pieces of survival and pride—most notably its women, who, in many ways, transcend the roles defined for them. In its staging of Gone With the Wind, we recognize it not only as a romance epic. It's a mirror—of the shame and glamour of America's past, and of the obstinate contradiction of those who lived. Mammy's voice, Scarlett's obstinacy, Melanie's sweetness, Rhett's world-weariness, all combined present an image of a society—and of a human race—trying to survive the gusts of change.